NCKU Study Challenges Classic Hypothesis on Mountain Species Extinction under Climate Warming — Published in Science

Limited evidence for range shift–driven extinction in mountain biota

Professor I-Ching Chen explained that mountain regions are biodiversity hotspots and are directly impacted by climate change. Scientists have long warned that mountain species may be riding an “extinction elevator”—forced to migrate to higher elevations in search of suitable temperatures, eventually running out of space and facing accelerated extinction. This newly published research is the first to globally and comprehensively test multiple predictions of the “extinction elevator” hypothesis, and surprisingly, found very limited supporting evidence. The findings open up entirely new avenues for future research.

The research team compiled elevation distribution data from 8,800 records, covering 23 mountain regions, 440 animal species, and 1,629 plant species—some data sets spanning over a century. Their analysis revealed that while species are indeed shifting upward due to warming, mountaintop species have not experienced significant declines. Additionally, species with narrow ranges and those from lower elevations are expanding their habitats upward, particularly birds. This range expansion has led to increased overlap among species and greater similarity in species composition across different elevations.

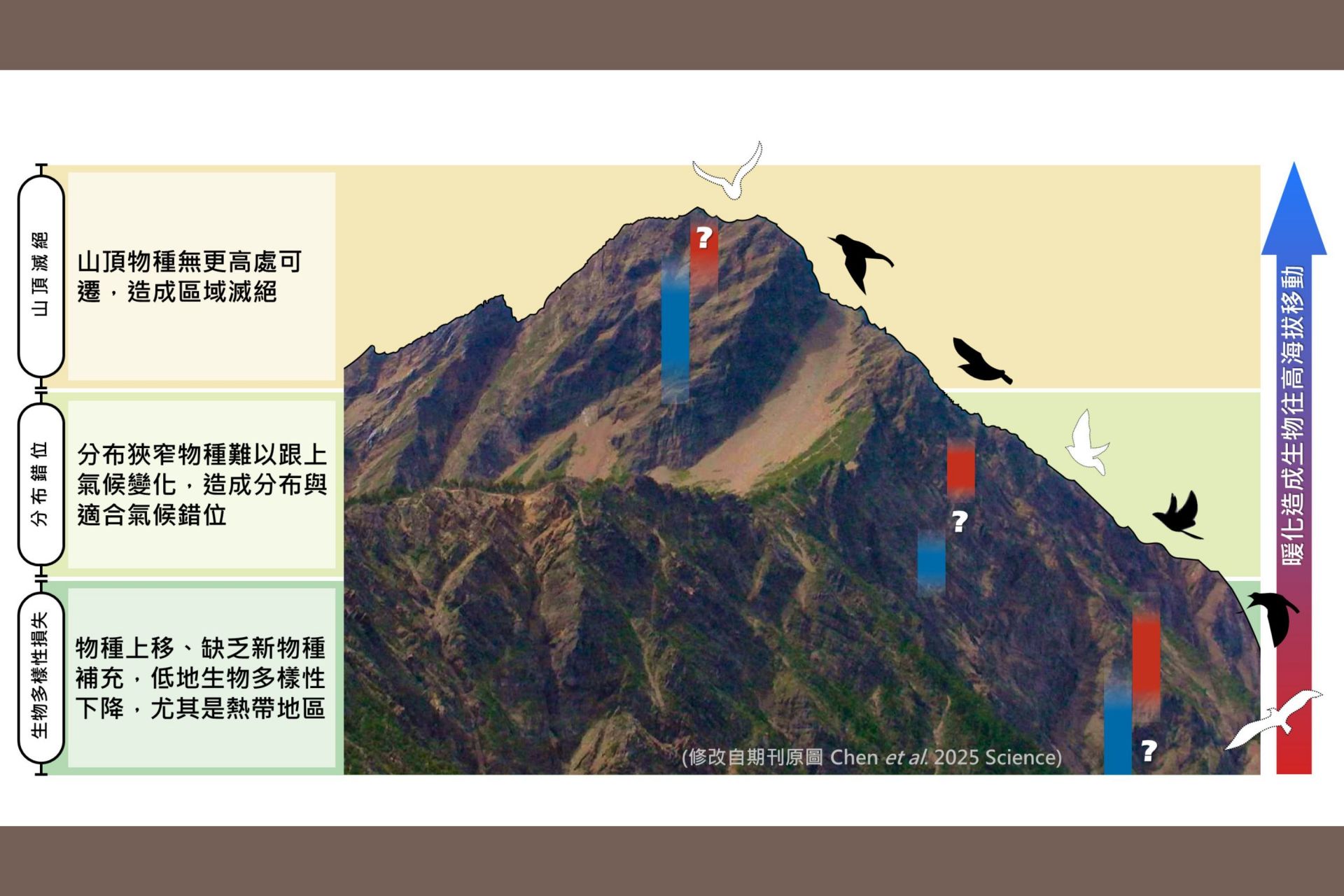

The “extinction elevator” hypothesis, proposed in the early 21st century, suggests that mountain biodiversity faces 3 major threats due to climate change: mountaintop species have nowhere higher to go, leading to extinction; narrowly distributed species cannot keep pace with shifting climates, resulting in a mismatch between their range and suitable conditions; and lowland biodiversity declines as species move upward without being replaced.

Dr. Yi-Hsiu Chen, postdoctoral researcher and first author, emphasized that none of the predicted outcomes of the “extinction elevator” hypothesis have clearly occurred so far. “Species responses are a much more complex story,” she noted. The study used advanced statistical models that account for geographic noise specific to mountain systems. 2 Bayesian multivariate models were employed to jointly analyze species’ upper and lower elevation limits, habitat ranges, and midpoint shifts—rigorously capturing the interactions among various factors, a level of analysis previous studies lacked. The team expressed great excitement about the recognition from such a top-tier journal.

Professor Chen speculates that because of the high biodiversity in mountains, species distributions may be constrained by interspecies competition, preventing them from occupying all available climate niches. Climate warming could be altering these competitive dynamics, contributing to the observed complex distribution patterns. This presents a stark contrast to models that consider only temperature effects. The resilience of mountaintop species suggests an adaptive response to climate, while the expansion of other species indicates a process of filling suitable climate niches. “This study significantly overturns previous assumptions and will reshape future research directions,” she said, including understanding how warming influences niche occupation, emerging species interactions, and whether mountains are accumulating an “extinction debt.”

The team cautioned that while species are still moving uphill, their delayed responses may result in an eventual “extinction debt”—a delayed biodiversity loss that is unavoidable and will eventually take its toll. For instance, observations in European mountains show lagging plant migration, suggesting that high-elevation ecosystems are in a temporary stable phase that will ultimately shift.

Professor Chen noted that this research is also highly enlightening for studying Taiwan’s mountain biodiversity. Taiwan is warming faster than the global average, leading to diverse biological responses. A 30-year repeat survey by the team found that Formosan Flat are expanding to higher elevations, while Formosan Lilacfork, already found at Taiwan’s highest peaks, have maintained their range. Other observations show that the Alpine Accentor, found along Taiwan’s ridgelines, are facing growing competitive pressure from species entering high-elevation habitats. Hence, future research should aim to understand how climate change alters species interactions and how such changes affect adaptive responses. From a conservation perspective, mitigating climate change remains the most fundamental approach. Conserving and reconnecting natural habitats—avoiding fragmentation—is essential to enable species to migrate and adapt to rapid climate shifts.

The study’s first author is Dr. Yi-Hsiu Chen (postdoctoral researcher at NCKU), with international collaborator Dr. Jonathan Lenoir (CNRS Researcher, Université de Picardie Jules Verne, France). The corresponding author is Professor I-Ching Chen of NCKU. The team extends their sincere gratitude for funding support from Taiwan’s National Science and Technology Council, the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency, and National Cheng Kung University.

Taiwan’s rapid warming is putting pressure on mountain ecosystems

/Photo credit: Yushan National Park Headquarters, National Park Service, Ministry of the Interior

Affected by warming, the elevational range of the Formosan Flat is expanding

/Photo credit: Wen-Chieh Lin

/Yushan National Park Headquarters, National Park Service, Ministry of the Interior

The Alpine Accentor, which inhabits the summit of Yushan, is facing increasing competitive pressure as more species enter high mountain environments

/Photo credit: Chia-Sheng Chen

/Yushan National Park Headquarters, National Park Service, Ministry of the Interior

Sightings of the Formosan Yellow-throated Marten, an endemic species of Taiwan, have continued to increase in mountain areas in recent years

/Photo credit: Yushan National Park Headquarters, National Park Service, Ministry of the Interior

Taiwan’s rapid warming has caused species distributions to shift toward higher elevations

/Photo credit: Ching-Yao Chiu

Professor I-Ching Chen (right) from the Department of Life Sciences at National Cheng Kung University and postdoctoral researcher Yi-Hsiu Chen (left) rigorously tested the “extinction elevator hypothesis” for the first time using global data. Their work challenges previous understandings of how warming affects mountain biodiversity, and the findings were published in the prestigious international journal Science

The prestigious academic journal Science published today (16th) the latest findings on how climate warming affects global mountain biodiversity, challenging classic hypotheses and drawing widespread attention

Professor I-Ching Chen from the Department of Life Sciences at National Cheng Kung University led a team to publish a study that, for the first time, used global data to comprehensively test multiple predictions of the “extinction elevator” hypothesis. Unexpectedly, the study found very limited supporting evidence, opening up a new perspective for future research